Van-Based First Aid:

Is It Worth the Cost?

First aid compliance is a workplace necessity, and businesses want a simple, reliable way to stay up to standard. That’s why van-based first aid services seem like an easy solution. They come to your facility, check your cabinets, restock supplies, and ensure you’re compliant. At least, that’s what they promise.

But is the convenience worth the cost? Many companies using these services are paying far more than they realize. This article breaks down the true cost of van-based first aid services, exposing where businesses are overspending and how they can take control of their own compliance without the extra fees.

The Hidden Costs of Van-Based First Aid

At first glance, these services sound appealing. They market themselves as the stress-free way to handle first aid compliance. But the real cost of these services is often hidden in unnecessary add-ons, inflated fees, and charges businesses don’t even realize they’re paying.

1. Service Fees That Add Up

Many businesses assume they’re only paying for first aid supplies. In reality, van-based providers tack on hidden service fees:

● A charge just for showing up, even if nothing needs restocking.

● Fees for AED inspections that could easily be handled in-house.

● Extra costs for simple tasks; some companies even charge for the wipes used to clean the cabinet.

2. Unnecessary Product and Overpricing

Another common issue? Overstocking. Many van-based services provide kits that exceed ANSI standards, loading cabinets with items businesses don’t actually need.

● According to OSHA, workplaces only need first aid supplies that meet ANSI Z308.1 standards, which means most businesses don’t require the expensive, oversized kits these services push.

● Fear-based sales tactics convince companies that “more is better,” leading to excessive spending on unnecessary supplies.

3. Costs That Fly Under the Radar

Van-based first aid services operate on low visibility. They don’t want customers to scrutinize invoices too closely. Instead, they work under the radar, bundling small charges into vague line items.

● Some companies don’t break down individual product costs, making it difficult to see exactly what you’re paying for.

● Many businesses never compare pricing because they assume they’re getting a fair deal.

● These services rely on automatic renewals, so companies keep paying without questioning the actual cost.

By the time businesses realize how much they’ve spent, they’ve already been locked into an expensive cycle.

The Smarter Alternative: Managing First Aid In-House

Staying compliant doesn’t have to mean paying for expensive service contracts. The ANSI Z308.1 standard clearly defines what a workplace first aid kit needs, and most businesses can meet these requirements with basic supplies and routine self-checks. By understanding the standard, companies can avoid unnecessary products and inflated costs.

Van-based services profit from the misconception that compliance is complex, but managing first aid in-house is easier than they want you to believe. Quick internal checks replace costly service visits, digital tools simplify tracking, and direct ordering eliminates hidden fees. Taking control saves money, ensures transparency, and keeps businesses from overpaying for services they don’t actually need.

How FC Safety Can Help

Van-based first aid services claim to simplify compliance, but they come at a high price. FC Safety offers a smarter, more cost-effective way to keep your workplace safe without wasting money.

● Cost-Effective First Aid Solutions: Stay compliant with ANSI-compliant first aid kits that include only what you need. No overpriced extras. Our transparent refill system ensures easy restocking with no automatic charges or hidden fees.

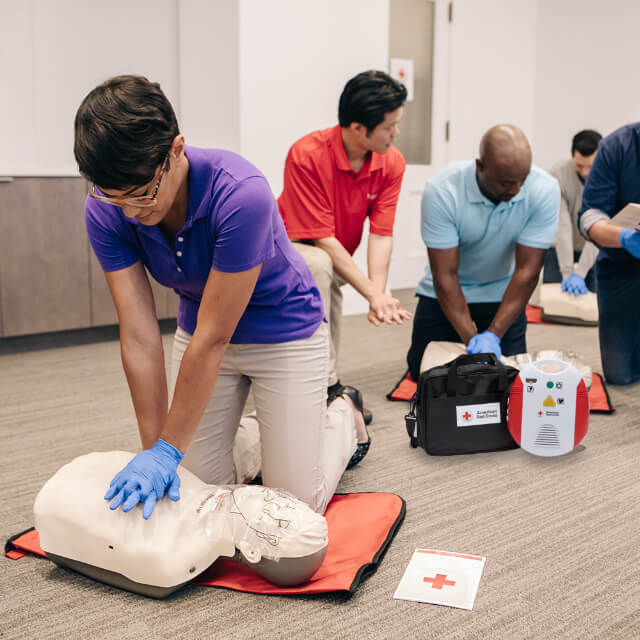

● AED Compliance Without Extra Fees: Our self-inspection tools make AED maintenance simple, eliminating the need for costly service visits. With clear, upfront pricing, you’ll never pay unexpected inspection fees.

● Full Transparency & Control: No surprise fees, no unnecessary add-ons. Just the supplies you need at a fair price. Our solutions empower safety teams to manage compliance with confidence and control.

Stop overpaying for first aid compliance. Take control with FC Safety’s straightforward, cost-effective solutions. Get started today.